easy keyg3nme

Date: 06/10/2025

Challenge URL: https://crackmes.one/crackme/5da31ebc33c5d46f00e2c661

Difficulty: 1.3

Architecture: x86-64

Language: C/C++

Platform: Unix/linux

Target File: keyg3nme

1. Introduction

1.1 Overview

“easy, you just need to figure out the logic behind key validation. this should be fairly easy even with an ugly debugger. i’m new here, so the difficulty ranking could be a little off.”

The target for this reverse engineering challenge is the executable file keyg3nme. This programs function is to act as a key validator.

1.2 Scope and Objectives

The objective, as hinted by the programs name, is to develop a key generator by reverse engineering its internal validation algorithm.

1.3 Tools and Environment

- Ghidra

2. Initial Analysis and Triage

2.1 File Information

File Hash

MD5: 84fd0728ae993ad998e22de7e0b5b0ff

┌──(kali㉿kali)-[~/crackmes]

└─$ md5sum keyg3nme

84fd0728ae993ad998e22de7e0b5b0ff keyg3nmeSHA256: c5a1a8b2545eb7868b26ca7dc79380cad8a0bfc01d1c53ce4f5e5c6662154a71

┌──(kali㉿kali)-[~/crackmes]

└─$ sha256sum keyg3nme

c5a1a8b2545eb7868b26ca7dc79380cad8a0bfc01d1c53ce4f5e5c6662154a71 keyg3nme

File Type

The file command is used to determine the file type.

┌──(kali㉿kali)-[~/crackmes]

└─$ file keyg3nme

keyg3nme: ELF 64-bit LSB pie executable, x86-64, version 1 (SYSV), dynamically linked, interpreter /lib64/ld-linux-x86-64.so.2, BuildID[sha1]=01d8f2eefa63ea2a9dc6f6ceb2be2eac2ca22a67, for GNU/Linux 3.2.0, not strippedFrom this output we’ve learned that the file is dynamically linked, meaning it requires external shared libraries at runtime. The interpreter is specified as /lib64/ld-linux-x86-64.so.2, which is the dynamic linker/loader responsible for finding and loading those required shared libraries.

Most importantly we also learn that the file is not stripped. This is the most crucial piece of information for reverse engineering. It means the file still contains its symbol table.

Symbol Tables

A symbol table is a data structure used by compilers, assemblers and linkers to store information about varies entities in a programs source code. Entities include: functions, variables and labels.

This information is saved within the compiled binary file.

These symbols are helpful when analysing the program in a disassembler or debugger, as they make the code much easier to understand than raw memory addresses.

ELF Headers

┌──(kali㉿kali)-[~/crackmes]

└─$ readelf -h keyg3nme

ELF Header:

Magic: 7f 45 4c 46 02 01 01 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00 00

Class: ELF64

Data: 2's complement, little endian

Version: 1 (current)

OS/ABI: UNIX - System V

ABI Version: 0

Type: DYN (Position-Independent Executable file)

Machine: Advanced Micro Devices X86-64

Version: 0x1

Entry point address: 0x1080

Start of program headers: 64 (bytes into file)

Start of section headers: 14816 (bytes into file)

Flags: 0x0

Size of this header: 64 (bytes)

Size of program headers: 56 (bytes)

Number of program headers: 11

Size of section headers: 64 (bytes)

Number of section headers: 29

Section header string table index: 28The only finding of note here is the ‘Type’ field within the header, we’ve now learned that the ELF type is ‘PIE’ or Position-Independent Executable (see References for further information). ‘DYN’ in this context stands for ‘dynamic’, as this ELF type is compiled to be loaded at a random memory addresses every time it runs.

This is a security feature and technique called Address Space Layout Randomisation or ASLR (see References for further information), this makes memory addresses unpredictable, meaning attackers can not rely on a single, static address to exploit for an attack.

2.2 Strings Analysis

Interesting Strings

Enter your key:

Good job mate, now go keygen me.

nope.These strings are likely used for human input, though nothing else was learned (for the full output see Appendices A).

2.3 Basic Execution

To form a better understanding of what we need to be looking for I execute the program.

┌──(kali㉿kali)-[~/crackmes]

└─$ ./keyg3nme

Enter your key: cracked

Good job mate, now go keygen me.

┌──(kali㉿kali)-[~/crackmes]

└─$ ./keyg3nme

Enter your key: 123456789

nope.

┌──(kali㉿kali)-[~/crackmes]

└─$ ./keyg3nme

Enter your key: test

Good job mate, now go keygen me.This confirms the findings from the strings command, however, the logic behind the responses originally confused me. It seems that we only recieve the ’nope.’ response if we do not include any alpha characters in the entered key.

After further analysis (section 3.2) it seems highly likely that this is a side-effect of how the input function handles mixed characters.

┌──(kali㉿kali)-[~/crackmes]

└─$ ./keyg3nme

Enter your key: Pa55w0rd

Good job mate, now go keygen me.

┌──(kali㉿kali)-[~/crackmes]

└─$ ./keyg3nme

Enter your key: Pa55&

Good job mate, now go keygen me.

┌──(kali㉿kali)-[~/crackmes]

└─$ ./keyg3nme

Enter your key: 67*7

nope.3. Detailed Reverse Engineering Methodology

3.1 Identification of Key Functions

The main function was easy to find and identify via the ‘Enter your key:’ string found; Ghidra makes finding and analysing these functions very easy.

3.2 Function-Level Analysis

main Function

undefined8 main(void)

{

bool bVar1;

undefined7 extraout_var;

long in_FS_OFFSET;

int local_14;

long local_10;

local_10 = *(long *)(in_FS_OFFSET + 0x28);

printf("Enter your key: ");

__isoc99_scanf(&DAT_0010201a,&local_14);

bVar1 = validate_key(local_14);

if ((int)CONCAT71(extraout_var,bVar1) == 1) {

puts("Good job mate, now go keygen me.");

}

else {

puts("nope.");

}

if (local_10 != *(long *)(in_FS_OFFSET + 0x28)) {

/* WARNING: Subroutine does not return */

__stack_chk_fail();

}

return 0;

}Below is a breakdown of noteable sections of the main function:

printf("Enter your key: ");This is a standard function to prompt the user for input.

__isoc99_scanf(&DAT_0010201a,&local_14);The scanf() function in C is used to read data from stdin and stores the result in the given arguments. In this context it reads the users input from the printf() function and stores the value. In the this code &DAT_0010201a is a string value and the format specifier and &local_14 is the variable where the value is stored.

Pointers

&DAT_0010201a is a pointer (memory address) to the format string stored in the static data section (.rodata or .data) of the program.

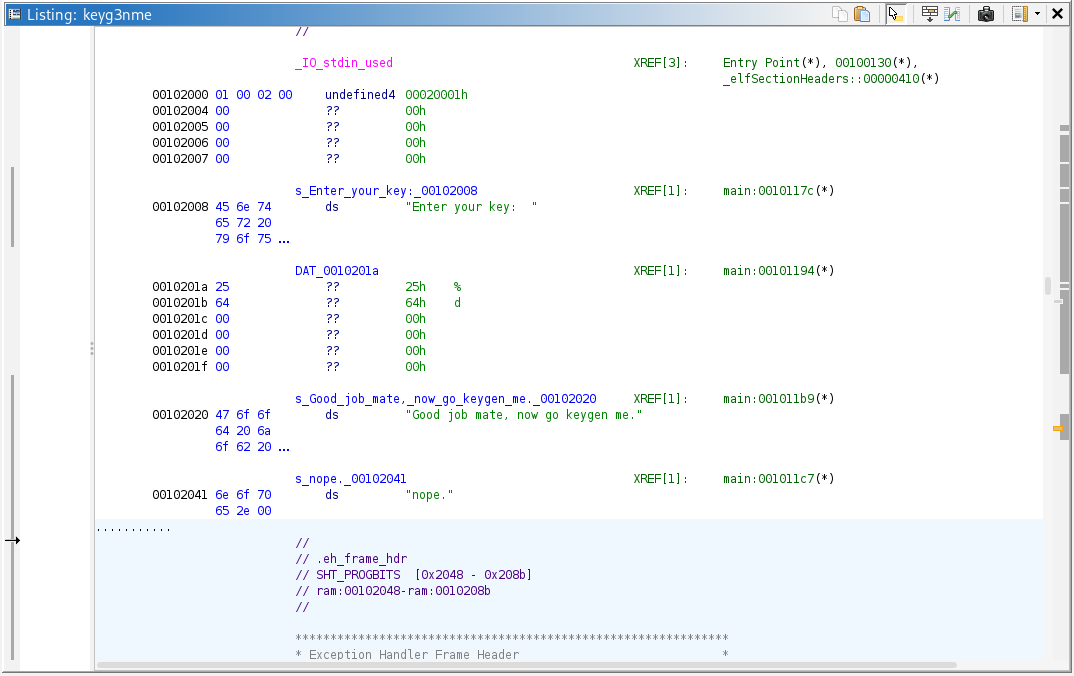

The symbol DAT_0010201a is a label that refers to the static data stored at the memory address 0x0010201a. Searching for this symbol provides us with:

DAT_0010201a XREF[1]: main:00101194(*)

0010201a 25 ?? 25h %

0010201b 64 ?? 64h d

0010201c 00 ?? 00h

0010201d 00 ?? 00h

0010201e 00 ?? 00h

0010201f 00 ?? 00hGhidra provides us with the ASCII values of the data stored in the memory addresses. We now know that the format required for the scanf function is ‘%d’, or a single decimal integer.

bVar1 = validate_key(local_14);This line of C tells us that the program uses the single digit integer that the user input and passes it to a function called validate_key().

We also know from an earlier line that this function returns a boolean value, as the bVar1 variable is a bool type.

bool bVar1;if ((int)CONCAT71(extraout_var,bVar1) == 1) {

puts("Good job mate, now go keygen me.");

}

else {

puts("nope.");

}This if statement checks if the bVar1 variable is euqal to 1, or true.

After much Googling, I found that the CONCAT71 and extraout_var are Ghidra artifacts related to how it handles the return value, these can be ignored and the statement can be simplified to:

if (bVar1 == 1)The program then prints the different strings depending on if the condition was met.

validate_key Function

bool validate_key(int param_1)

{

return param_1 % 0x4c7 == 0;

}Below is a breakdown of the code:

bool validate_key(int param_1)The function takes in the previously passed integer and will return a boolean value param_1.

return param_1 % 0x4c7 == 0;The users input - param_1 - is divided by the value of 1223 (or 0x4c7 in a hexadecimal format). The Modulo operator (%) is used to pass the remainder of this division onto the conditional check.

This condition checks that the remainder is 0, if the key passes this check 1 (or true) is returned to the main function, otherwise 0 (or false) is returned.

4. Conclusion and Solution

4.1 Summary of Findings

Analysis of the programs decompiled code fully revealed the key validation mechanism.

The main Function Overview

The main function executes the programs basic flow, which consists of three main steps: prompt, input validation, and result output.

- Input Type:

Examination of the__isoc99_scanfcall, and specifically the format string stored atDAT_0010201a(0x0010201a), confirmed the raw data to be%d\0(hex:25 64 00). This is a critical finding, confirming that the program expects the users key to be a single decimal integer. - Validation Path:

The input integer is immediately passed to the core logic function:bVar1 = validate_key(local_14);. - Success Condition:

The program prints the success message “Good job mate, now go keygen me.” only if the boolean return value (bVar1) fromvalidate_keyis equal to1.

The Key Validation Algorithm

The validate_key function - the target of this analysis - is straightforward:

bool validate_key(int param_1) { return param_1 % 0x4c7 == 0; }

- Operation:

The function takes the users integer key (param_1) and applies the modulo operator (%) with a hardcoded hexadecimal value0x4c7. - Condition:

The key is considered valid only if the remainder of this division is exactly zero. - Required Divisor:

The hexadecimal value0x4c7converts to the decimal integer 1223.

$$ (4C7)₁₆ = (4 × 16²) + (12 × 16¹) + (7 × 16⁰) = (1223)₁₀ $$

(I did not calculate this).

4.2 Final Key/Solution

The only requirement for a valid key is that it must be a multiple of 1223. The key generation algorithm is therefore simply:

Valid Key=N×1223, where N is any positive integer.

The simplest valid key is 1223, or 0.

Back Matter

References

- ASLR - Wikipedia: Address Space Layout Ranomisation

- PIE / POC - Wikipedia: Position-Independant Code

Appendices A

The full command output of the strings command.

┌──(kali㉿kali)-[~/crackmes]

└─$ strings keyg3nme

/lib64/ld-linux-x86-64.so.2

libc.so.6

__isoc99_scanf

puts

__stack_chk_fail

printf

__cxa_finalize

__libc_start_main

GLIBC_2.7

GLIBC_2.4

GLIBC_2.2.5

_ITM_deregisterTMCloneTable

__gmon_start__

_ITM_registerTMCloneTable

u/UH

[]A\A]A^A_

Enter your key:

Good job mate, now go keygen me.

nope.

;*3$"

GCC: (Ubuntu 8.3.0-6ubuntu1) 8.3.0

crtstuff.c

deregister_tm_clones

__do_global_dtors_aux

completed.7963

__do_global_dtors_aux_fini_array_entry

frame_dummy

__frame_dummy_init_array_entry

keyg3nm3.c

__FRAME_END__

__init_array_end

_DYNAMIC

__init_array_start

__GNU_EH_FRAME_HDR

_GLOBAL_OFFSET_TABLE_

__libc_csu_fini

_ITM_deregisterTMCloneTable

puts@@GLIBC_2.2.5

_edata

__stack_chk_fail@@GLIBC_2.4

printf@@GLIBC_2.2.5

__libc_start_main@@GLIBC_2.2.5

__data_start

__gmon_start__

__dso_handle

_IO_stdin_used

__libc_csu_init

__bss_start

main

__isoc99_scanf@@GLIBC_2.7

__TMC_END__

_ITM_registerTMCloneTable

validate_key

__cxa_finalize@@GLIBC_2.2.5

.symtab

.strtab

.shstrtab

.interp

.note.gnu.build-id

.note.ABI-tag

.gnu.hash

.dynsym

.dynstr

.gnu.version

.gnu.version_r

.rela.dyn

.rela.plt

.init

.plt.got

.text

.fini

.rodata

.eh_frame_hdr

.eh_frame

.init_array

.fini_array

.dynamic

.data

.bss

.comment